So what constitutes a GOOD STRING JOB asked several players this past week?

The tournament pros are absolutely fanatical about their choice of strings and the associated string tension — which they change to suit both surface and playing conditions — and often during a match. I still carry two rackets in my bag each with a slightly different tension to accommodate the changing playing conditions at Manly Lawn.

Conversely, our average tennis player puts what I euphemistically call “two dollars worth of nylon” in a $200+ high performance frame — and expects to play consistently well and without injury, especially tennis elbow.

Most club players who play two or more times a week are well advised to get a GOOD STRING JOB every 8 to 10 weeks depending on the season. Aggressive players who blast the ball with big western forehands (Andrew, Bosko, Harry & Co) need to update every 3 to 4 weeks or so. Yep, strings go loose and dead — and performance suffers!

Trust me when I say, your game will improve at least a POINT A GAME with a good restring! You might even be encouraged to take a few lessons to help better manage the rest of your limitations.

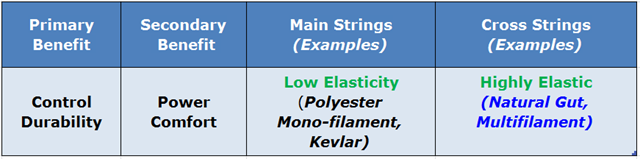

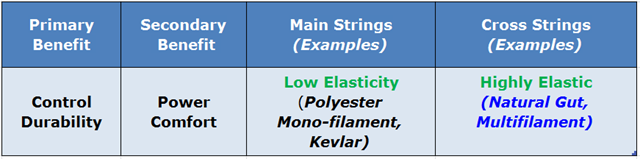

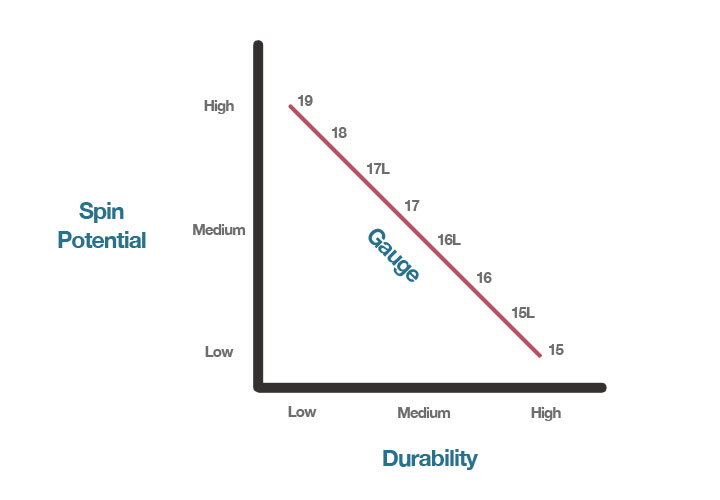

First a little science education since modern strings come in different materials and thicknesses, each designed to suit different playing styles. In the table below, you’ll notice the differences in the main and cross strings and the dependence on whether you want control, power, comfort (did I mention managing tennis elbow?).

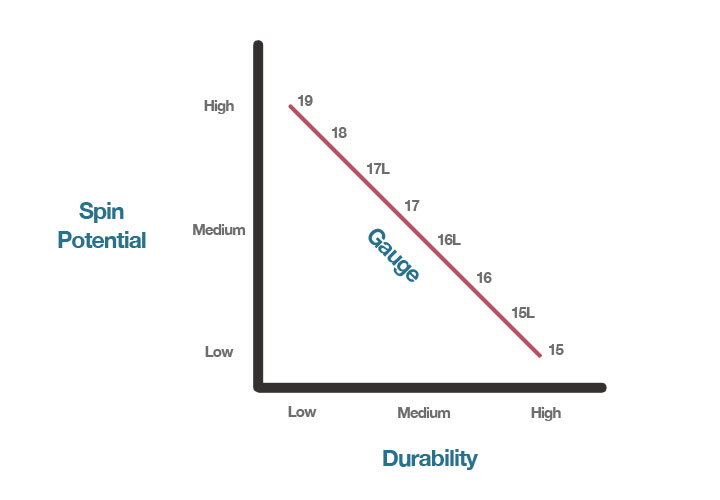

Thickness is pretty screwy since 18 gauge string is thinner than 16 gauge, go figure!

You can see from the graph above that the typical $2 nylon (16G) has high durability (to ensure rackets have a good shelf life) and low spin potential ( aka “feel/control”)! How did that new Wilson play Jordan with the $2 nylon??

Even at my tender age, I still use a hybrid combination of 18G multifilament Gamma Live Wire on the mains and Babolat Blast (Nadal’s string) on the crosses. Yep as I’ve aged and reverted to social player status, I’ve gone for more control and less power by reversing the mains and the crosses per the table. The 18G Live Wire is more lively (plays like gut) and gives me much more feel. The Blast allows me to give the ball a nudge and more topspin when I need to (sorry Richard).

And now the string tension. Most players string the crosses the same as the mains and expect the tension to be even itself out throughout the racket during stringing. Well that’s the logic anyway. The GOAL was always to get an even string tension in the racket to increase the ‘sweet spot’. Yep, for most of my playing life I relied on that logic too. Of course my ball watching was so much better than, and I played with gut, so miss hits were infrequent. And yep it’s SOoooooo Wrong!

Several years ago I ran into a older, chain smoking racket stringer in California who set me straight — and he didn’t hold back! Turns out that what most people miss is the impact of FRICTION on the Crosses when you’re feeding the string under and over through the Mains. Whatever tension you string the Mains at, you ADD 5lb to the Crosses to counter the friction. Here’s my current stringing pattern to illustrate this key point:

So Obi Wan (thanks Howard) how should I translate this to my game? Well most rackets come with a suggested stringing guide for tension. Start with the mid range for the racket for the Mains and then string the Crosses 5lb more. Then adjust up and down as required until you’re comfortable with the tension. Aside, typically you can use a lower tension that the one you used previously; helps your feel and control.

Just ask Tommie for ‘Rob’s restring’ if you want to try this type of restring at the Manly Tennis Centre. You’ll find an immediate benefit of a bigger sweet spot — and most of your misshits will go over now as your control is significantly improved. Just ask Howard, Ken Grey or some of our other playmates what the effect has been on our games!

As for the choice of string, well that depends on your game. I’ve given you the guidelines in the table above which you can probably figure out yourself. Even so, probably better to go talk to Scottie, Tebbs or Howard when you want some pro advice about what strings may suit your individual playing style.

To repeat what my mate Howard the pro says, you’ve got to manage your limitations — and using better technology (whether frame and/or strings) is a great way to do this. Cunning and guile will only get you so far! Invest in the technology!

Make a regular investment in a GOOD STRING JOB using the latest materials technology; it’s absolutely worth it for your psyche alone!

Sincerely,

Rob

USPTA